A Dozen Bright Dots

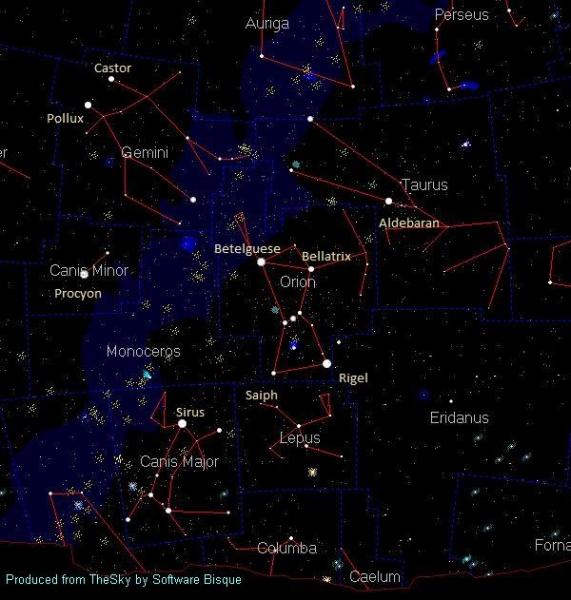

There is something about cold winter nights that make the stars shine a bit brighter than usual. Could it be the lack of haze – the kind we experience on sultry July and August nights? Or could it be the fact we can only last for a short period in the extreme cold? These are all valid reasons but the fact of the matter is Orion the Hunter and its neighbouring constellations represent a dozen of the brightest stars in the winter sky.

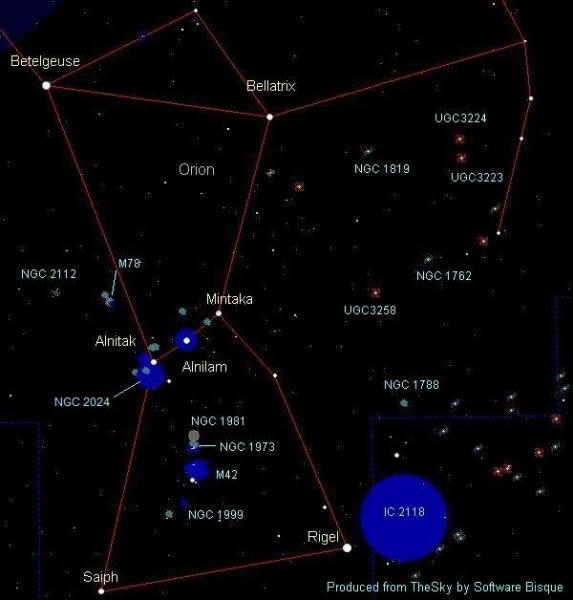

Half this number makes up Orion’s body from his shoulders down to the knees. Others are labelled on the chart below. Orion is one of - if not the most observed constellation. With its belt stars lying on the celestial equator, both hemispheres of the Earth have a chance to see the hunter in action as he battles Taurus the Bull. The obvious favourite target for telescope or binoculars is the great Orion Nebula. Also widely known as M42, this 4th magnitude cloud can easily found in light-polluted suburbs. Within the confines of the cloud located 1,500 light-years from us, pockets of gas and dust are slowly condensing and growing to produce hundreds of stars. The immense glow lighting up this 45 light year wide cloud comes from the ultraviolet radiation from newly developed young stars. This stellar nursery is known as an emission nebula.

Another example of an emission nebula is The Flame Nebula. NGC 2024 is located a little northeast of the left-most star of Orion’s belt called Alnitak. The Flame is only a symbolic name as there is no fire in space. NGC 2024 is a combination of emission and reflective nebulas. The obscuring dust in the middle of the gas cloud is blocking the brightest portion of the star-making region and give the appearance of fire. NGC 2024 is the same distance from us as the Orion Nebula. The Horsehead Nebula located below the Flame is very difficult to see visually.

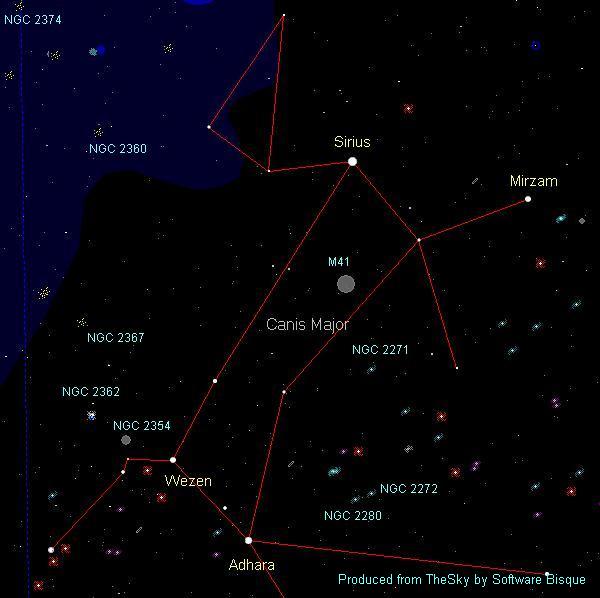

Of this dozen brilliant suns, the star Sirius is by far the closest and brightest. Our world and Sirius are separated by a mere 8.6 light-years. In other words, if an alien observer around Sirius were to use a powerful telescope to spy on our daily lives here on Earth, it would see events from September 2002. We are always looking at the sky in the past.

The name Sirius is derived from the Greek word ‘scorching’ or ‘glowing’. Sirius is deemed as the eye of Orion’s great hunter dog, Canis Major with Canis Minor being his other faithful beast. Sirius was used as an indicator of the change of seasons and that the Nile River would soon flood because of seasonal change. We even refer to this star in the term “dog days of summer”. Early civilization believed the heat of this star in conjunction with the July Sun, produce hotter days than usual. Other than being the brightest star in the night sky blazing at magnitude (-1.46), Sirius has a tiny companion star called Sirius B. Unlike other double stars you have seen, Sirius B will be a real challenge to spot. At magnitude 8.6 it is some 10,000 times fainter than Sirius A.

Located some four degrees directly below Sirius is a lovely magnitude 4.6 naked-eye open star cluster called M41. At first glance, this cluster is only populated by a couple of dozen stars spread out over an area the size of the full moon but about 100 suns live in this cluster. Some of its members comprise of orange and red giant suns. M41 is 2,300 light-years from us, measures about 25 light-years wide and was first noted by Aristotle in the year 320 BC.

And now for something farther out in space – a lot farther. Look for NGC 2280 which 3.3 degrees west of the star Adhara. NGC 2280 is a spiral galaxy with a delicate arm structure. This galaxy has an estimated distance of 75 million light-years from us. In other words, dinosaurs were still roaming on Earth and hunting for food when the light left this object. Measurements indicate the galaxy is 140,000 light-years wide.

From February 22 and for the next two weeks, start looking for the faint zodiacal lights on the western horizon. We witness this glow around the spring equinox in the west and the fall equinox in the east. The light is the scattering of interplanetary dust. We get to see this display from dark sites away from light sources and with the absence of the moon. Looking at these particles is like looking along the surface of a dark tabletop that has not been dusted for a week or two.

Jupiter is slowing regaining its lost belt. This will be your last month to get your final views of the king of planets. Jupiter will set at 9 p.m. local time on the 1st and by 7:30 at month’s end. Get your cameras ready for a nice Kodak moment on February 6th and again on the 7th as the Moon slides to the right of the planet. This was a good season to observe and photograph this great planet. We even witnessed the disappearance of a previously mentioned belt. By July – Jupiter will be twelve degrees higher in declination than it is now. Less atmospheric turbulence equals better observations and photos.

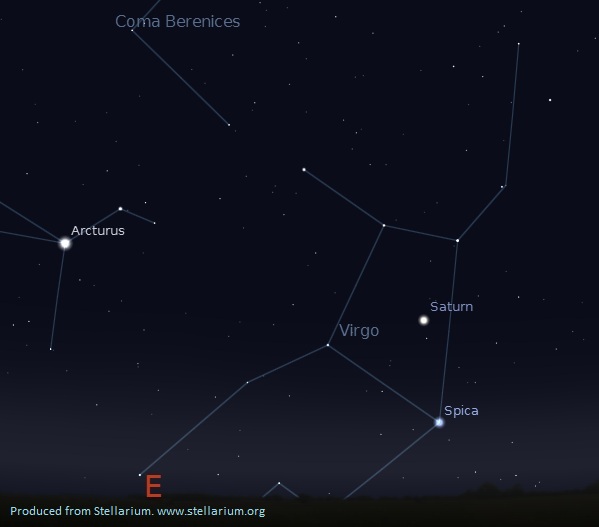

The planet Saturn is nice up in the southeast by midnight local time. Do not get confused with brilliant white coloured Spica located eight degrees south of yellowish Saturn. Before Christmas, Saturn developed a storm in its atmosphere. It has now escalated in a monster. See is you can spot this storm from one and a third billion kilometres away.

The planet Venus still dominates the morning sky but is slowly sinking to the horizon. On February 1st Venus crosses into Sagittarius from Ophiuchus and will stay here for the entire month. On the morning of February 4th, you will find Venus nestled between clusters M21 and M23. The best conjunction with the 16 percent waning crescent moon will be on the morning of the 28th. To help plan your observing sessions this month, the Full Cold Moon will occur on the 18th. If you have questions or comments, feel free to contact me.

Until next month, clear skies everyone.