Southern Skies

I was recently listening to some vintage country music by Glen Campbell. He was singing “Southern Nights” which is one of my favourites. This song was a big hit for him in March 1977 as it held the number 1 position in Billboard magazine for two straight weeks. Midway through the song, we hear the lyrics “Southern Skies, have you ever noticed Southern Skies. Its precious beauty lies just beyond the eye …..” and this is so true. As we venture outdoors on these warm July nights, we cast our eyes and telescopes south to the center of our home galaxy called the Milky Way. The mysterious grey veil stretching high in the night down to southern skies is the collective glow of millions of distant stars of our galaxy. Some of these suns are so far, they cannot be resolved with a telescope.

With the celebration of the summer solstice, this past June 20th our nights are now slowly getting longer. At the beginning of July nautical twilight does not end till about 10 p.m. locally and for those living in Canada’s north, it does not get dark enough to observe. The three flavours of twilight (not the vampire series) seen after sunset or before sunrise is: civilian - when the sun is located six degrees below the horizon, nautical - when the sun located twelve degrees below and astronomical - when our day time star is situated 18 degrees below the horizon. Astronomical twilight occurs a little more than two full hours after sunset and the same amount of time before sunrise. With such a short observing window, this time of year is not kind to astrophotographers who rely on the darkest hours to collect photons.

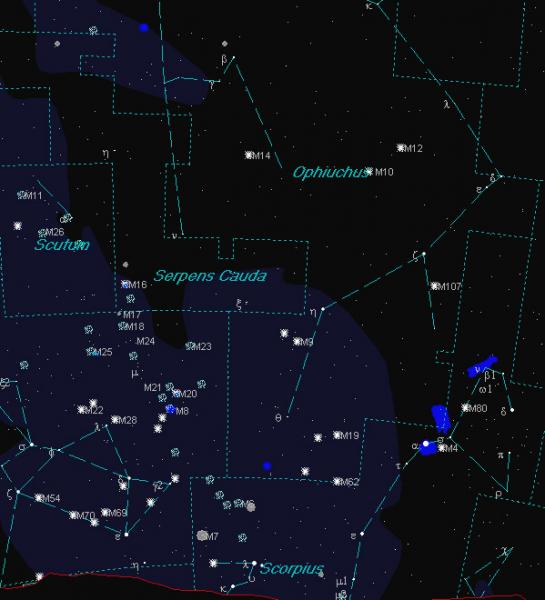

However, part of the fun of preparing the night’s observing session is watching the brightest stars pop into view as twilight creeps on. The opposite occurs in the morning as the sky lightens. Before the sky gets too light, lock on a very bright star and see how long you can follow and observe it even with the sun up. For the next few months, you should have no trouble picking out an orangey-red star low in the south as the sky darkens. This star is called Antares and depicts the heart of Scorpius the Scorpion. At about midnight on Canada Day, Scorpius reaches its highest point on the meridian and then by 10 p.m. by month’s end. Even at its highest assent in the south, Canadian locations still miss a bit of the creature’s tail as it curves down and never rises above the horizon.

Antares is a huge star, tipping the scales at 12,000 times brighter than our Sun. If this supergiant star was placed at the center of the solar system, it would almost extend to the orbit of Jupiter. Antares is in an area of many globular and open star clusters. And no wonder, it is only 18 degrees to the west of the galactic center. A mere 1.3 degrees to the right of Antares is M4. Wider than the full moon, this magnitude 5.6 loose globular is one of the closest to us. At only 7,200 light-years away, you should be able to spot it naked eye from a dark site. If you have a wide-angle eyepiece that includes Antares and M4, you should also pick up a smaller globular called NGC 6144. This globular cluster measures about a third the size of M4 and is centred between the two to form a triangle.

Extending north from Antares is the largest complex in the entire sky. It is known as the Rho Ophiuchi Complex Cloud and is located on the Scorpius – Ophiuchus border. Stretching an astonishing four degrees in height Rho Ophiuchi is a treat for astrophotographers. With the mix of colour, texture and surrounding objects, Mother Nature did a great job constructing this lovely stellar portrait.

One object that needs no optical aid is M7 located by the stinger. Measuring only 800 light-years from us and about 20 light-years in width, this magnitude 3.3 open star cluster easily stands out amongst the others. About 80 suns call this object home. Move up about six degrees from M7 in Sagittarius and you are viewing the heart of the galaxy. A majority of the Milky Way’s 157 globular clusters hover around the nucleus of the galaxy like bees around a hive. For all intents and purposes, there are no galaxies located within Sagittarius, just balls of stars.

There are however a few interesting nebulae to track down and observe. First, we will look at M8 aka the Lagoon Nebula. This emission nebula is what astronomers refer to as a stellar nursery with immense clouds of gas and dust measuring light-years across, collapsing onto itself to eventually create stars. Our own Sun began this way some five billion years ago in our own solar cocoon to which the leftover material formed our planets.

M8 easily measures twice the full moon in width and another lunar diameter in height. At just the limit of naked-eye visibility, M8 can be glimpsed naked eye from dark sights but any kind of optical aid will help. The Lagoon is located 5,200 light-years from us. Along with the distinctive red nebulosity depicting hydrogen gas, it also has a young cluster catalogued as NGC 6530 in tow which astronomers date as about a million years old. The simplest way to locate M8 is to find the K0 giant star Alnasl at the tip of the Teapot and move straight up six degrees. Once you finished examining the Lagoon nudge for scope up one and a third degrees and a bit to the right will you come to M20 – the Trifid Nebula. The Trifid is actually a combination of emission and reflection nebulas. Photography will reveal the offsetting colours of the red emission and the blue reflection nebula. M20 resides roughly the same distance as Lagoon. With a low surface brightness, the Trifid is a full three magnitudes fainter than the Lagoon.

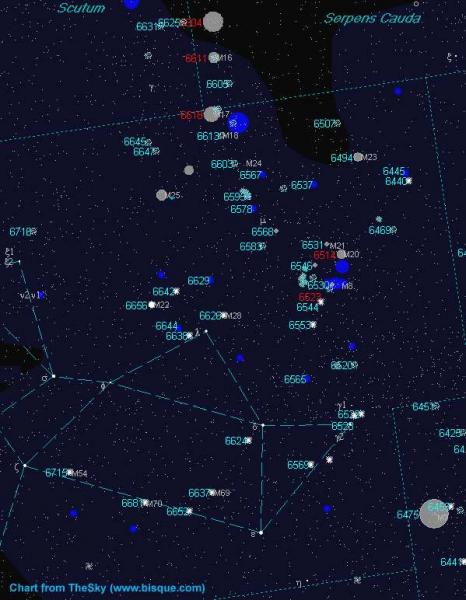

Moving up the veil of stars we come to a huge association of stars. The M24 Star Cloud is just that. It is not a round ball of stars we have previously seen nor is it a star-forming region. M24 is a pseudo-cluster that stretches for thousands of light-years and runs along the galaxy’s arm and is similar to the NGC 206 star cloud in M31 - the Andromeda Galaxy.

Keep moving up to the very northern boundary of Sagittarius we come across another stellar nursery call the Swan or Omega Nebula. It has even been called the Horseshoe or Lobster Nebula. With all these aliases, Charles Messier simply catalogued it as M17. This target is about a third the size of the full moon but is still at naked eye limits. At a bit shorter range of 5,000 light-years, the Swan has enough star stuff to make a very nice open cluster containing hundreds of suns.

Before you leave Sagittarius, locate the magnitude 4.6 open cluster M25. This is now your guidepost to tracking down the minuscule planet Pluto. With an orbital period of 248 years around the Sun, it is not moving very fast. However as earth speeds away in its orbit, Pluto is in retrograde or moving westward across the sky until the middle of September. It so happens, this motion to the right will have Pluto swing under the M25 from July 15 – 30. You will now have a few more guide stars to use in spotting this teeny tiny object.

It was only four short months when the two brightest planets of our solar system was putting on a great evening show. Around mid-March Venus was nicely placed above Jupiter. Now as July opens, we see a complete change of planetary order. The early morning sky now shows Venus on the bottom with Jupiter to the upper right. Framed with Aldebaran to lower left and the Pleiades to top right, you should really set the alarm clock early and capture this nice digital moment. Venus achieves greatest brightness of minus 4.7 on the 12th.

Saturn and Mars are on their last couple of months viewing before they are lost in the solar glare. At the beginning of July Mars will set in the west at 12:20 a.m. and Saturn at 1:30 a.m. local time. By months end their set times shorten to 10:50 p.m. and 11:20 p.m. respectively. Mars is moving quickly eastward and will slide between the ringed planet and the star Spica on August 14. Even our planet made this month’s article. On July 4 the Earth will be at its farthest point from the Sun at 152,092,400 km.

The full Thunder Moon occurs on July 3 at 14:52 EDT and the new moon is slated for July 19 at 00:24 EDT. The next day on the 20th marks the 43rd anniversary of Apollo 11 landing on the surface of the moon.

Until next month, clear skies everyone.