Glowing Suns By The Million

Have you ever just looked up into the night sky? Not to search for a faint nebula nor to split a close double star. Not to polar align an equatorial telescope or estimate the limiting magnitude of the night. It is just as it sounds, look up. If you have ever found yourself in the countryside on a moonless clear night and away from any kind of distracting stray light – you know exactly what I mean.

No words can describe the feeling of awe when your eyes rise up and catch the glow of the night above. Stretching from the W shaped Cassiopeia the queen in the north, we begin to feel of sense of haziness. It is not high cirrus cloud or the smoke of a local campfire (although it might be by coincidence). We continue to follow this glowing path to overhead and all the way to the southern horizon. Comparable to looking at a dusty tabletop along its surface level, here we catch the cosmic glow of millions of distant stars. This is the plane of our home galaxy called the Milky Way.

Our Galaxy has an estimated population of some two hundred billion stars, stars just our Sun. Cool September nights are prime to see the Milky Way high overhead. As time marches on after the Sunsets, the sky darkens to a deep blue; one by one the stars come out to play until the sky is filled with stellar dots.

With today’s digital DSLR cameras, one can capture the beauty of the night with very short exposures. Simple tracking mounts such as a barn door or hinge mount can help compensate the Earth’s motion, yielding pinpoint stars. In the old days, single five-minute images were required to bring out the path of the galaxy and hope the tracking was spot-on accurate.

The most popular film had a light sensitivity of ISO 400 or 800. DSLR cameras now reach speeds of ISO 1600 and 3200. In the digital age, one can take a single five-minute exposure if they are confident the tracking is good or five – one-minute exposure which is then digitally stacked or co-added. Free software such as Registax 5 can easily accomplish this.

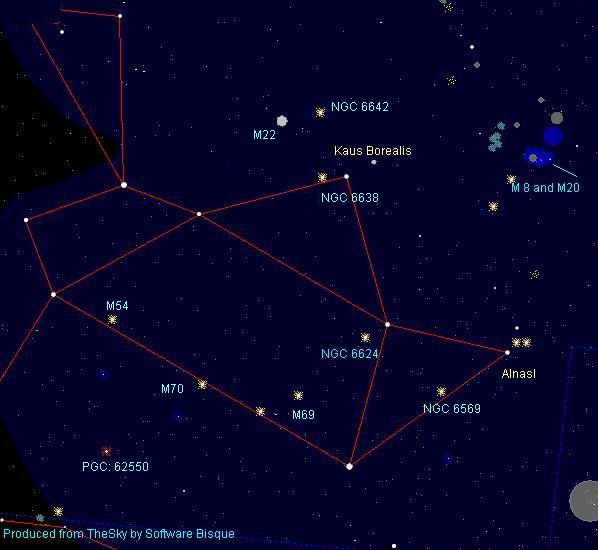

Down in the southernmost region of the Milky Way in the constellation Sagittarius – the archer. The eight prominent stars form an imaginary Teapot. This asterism depicts the four stars of the handle on the left side and a triangle of suns forming the spout to the right.

There is a fabulous globular cluster that is one of many that reside in Sagittarius. M22 is a wonderful splash of evenly bright stars. I can watch this cluster for hours. At a little more than 10,000 thousand light-years from us, its estimated population of 70,000 suns spanning a width of 97 light-years appear as wide as the full moon in the sky. Hunting for M22 is not that difficult. First, locate Kaus Borealis at the top of the teapot. Now move your scope to the left 2.5 degrees or a couple of star fields of view. M22 should be an easy target in the finder.

Let us now look at a few other objects in the region. Move to the right until you get to the end of the spout. This star called Alnasl is a class K giant that lies 96 light-years from us. From here, look up about twelve full moon widths or six degrees until you locate a horizontal patch of light. The object is M8 or the Lagoon Nebula. Commonly referred to as a stellar nursery, the Lagoon is one of the brightest star-forming regions in the entire sky. This gigantic cloud of gas and dust measures 140 light-years long and 60 light-years wide. It lies some 5,200 light us and is right on the border of naked-eye visibility. Any telescope will reveal its gas cloud as well as a very young cluster of stars. Look for the dark lane of material running from left to right.

Move your scope a little north and a little west to reveal yet another star-forming region. The Trifid or M20 lies the same distance as the Lagoon Nebula but is 50% fainter. Its colourful and delicate takes on the appearance of a flower. Photography will show this portrait in two colours. The young stars in the center of the emission nebula, light up the area in traditional red, whereas the reflection nebula takes on a pastel of blue.

Throughout Sagittarius, numerous open and globular clusters pop into view. You will not see any galaxies in this region as we are looking into the thickest part of the Milky Way Galaxy. You will, however, see patches of dark clouds, which carry catalogue number from E.E. Barnard. These dark areas are very wide and only require 7 X 35 wide-field binoculars to spot and enjoy. Again, digital photography will help reveal these smudges of black.

I hope you had success last month in locating the planets of our solar system. Most are still around but Saturn is losing the battle with solar glare. Mars, on the other hand, is taking its time and slowly moving into the glare. On September 1st Mars will still be some forty-two degrees from the Sun but pretty well stay north of brilliant Venus. By month’s end, the red planet’s distance shortens to thirty-two degrees.

Jupiter will be at opposition on the 21st and is still one equatorial belt short. When a planet is at opposition, it rises in the east as the Sun sets in the west and opposite at sunrise. This is also when the planet and in this case Jupiter, will be closest to Earth which allows us to see better detail. As the years go by, Jupiter is rising on the ecliptic, astrophotographers are taking advantage of better conditions as opposed to a couple of years ago when Jupiter was down in southern skies. Consult pages 234 and 235 of the 2010 Observer’s Handbook of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada for the timing of Jovian satellites as they pass in front of the mother planet and cast shadows on to the frozen clouds.

Air turbulence played havoc with Jupiter’s light. However, happier times are here again. Uranus – located to the west of Jupiter is also at opposition but thanks to its incredible distance, no detail would be seen whatsoever.

The full Harvest Moon will occur on September 23rd which by coincidence is also the fall equinox which occurs at 3:09 UT. Now we see the night hours lengthening and day hours shortening.

Until next month, clear skies everyone.